There is a great deal of documentation (both in the product Help and on this blog) which describes how planned maintenance can be managed using e-Quip. I thought that it might be useful to provide a brief overview of these techniques to act as a roadmap to point you in the direction of the right bits of documentation. This article is a “work-in-progress”. Planned maintenance is not the most interesting subject in the world for a blog and as I periodically lose the will to live I may take brief breaks from it! If and when it’s finished I will probably tidy it up and try to make it more of an easy read.

When it comes to equipment maintenance there are several basic strategies which each have their own benefits and limitations. It is rare that one approach is suitable for your entire inventory, so most of our users operate a hybrid system with different strategies for different situations.

What is your Goal?

Most device managers will have some kind of plan which controls how and when devices should be serviced. This seemingly straightforward statement hides a great deal of detail, both in the goal of the plan and the strategy for implementing that goal. You may be familiar with Medical Device Bulletin DB2006(05) Managing Medical Devices. In the Legal Liabilities section (Section 8.8) this publication states:

The responsible organisation should take all reasonable steps to ensure that equipment is repaired and maintained appropriately. The extent of liability will depend on the specifics of the case, and what steps are taken to ensure that adequate repair and maintenance is carried out.

The key words here are reasonable, appropriately and adequate. Legislation always includes words like these so that lawyers can earn pots of money arguing about what they mean. In such cases courts often refer to “the man on the Clapham omnibus”, and what he would consider to be appropriate or adequate. I will rely heavily on this chap throughout this article.

Your goal might be something along the lines of:

a) To maintain the devices that you are responsible for in a way which the man on the Clapham omnibus would consider to be approriate

b) To apply sufficient diligence to the execution of your plan that this same man would consider reasonable

c) To keep sufficiently detailed records that you will be able to convince this chap that you have done both a) & b).

From this goal you will produce a plan. This may seem obvious, but your plan shows how you intend to achieve your goals. It is very easy to come up with a plan, and for you to comply 100% with that plan, and yet still not achieve your goals. It is also worth bearing this in mind when you produce KPI’s: should they indicate how well you are keeping to your plan, or how well you are achieving your goals?

A relatively common goal would be to maintain all of your medical devices in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions at the intervals specified by the manufacturer. Of course, as a professional engineer you are free to override this using your professional judgement. Certain manufacturers may “over-egg the pudding” somewhat, simply to generate revenue. If Peugeot specified that my car should be serviced every day, then I’m sure that this much put-upon chap in Clapham would agree with me that this is neither reasonable, nor appropriate.

How Hard should you try to Attain that Goal?

We all live and work in the real world, and the real world comes with all sorts of constraints and practicalities. If your plan says that device “X” should be serviced on 1/1/2013, how much effort should you expend in trying to achieve this? Should you service it or die trying? Should you close the hospital if you can’t find it, or maybe just close a couple of wards? The bloke in Clapham might consider this to be a bit of an over-reaction, especially if the device in question is a tympanic thermometer.

Similarly, you may well be able to find device “X”, but if that is just 1 of 10,000 devices which need to be serviced then you may have insufficient resources to do all of them. Should you close the hospital until you have done them? Can you delay the service by 1 month, possibly 2? How about 12 months? You could take the Alan Rickman approach and “Call off Christmas!”. I suspect that the answer would be different if the device was a tympanic thermometer or a defibrillator. By the way, if you haven’t ever seen Robin Hood Prince of Thieves, then it’s worth it just to hear Alan Rickman saying “Call off Christmas!”, and also to see the hero land at Dover and exclaim”Tonight we dine at my father’s house in Nottingham”. Presumably the Dover to Nottingham rail link was better then than it is now!

It is a simple, unavoidable fact that some devices may be impossible to find. If the device has been stolen or lost then you can search as much as you like but you won’t find it. Clearly you need to decide how much effort is reasonable, and for most device managers, the definition of reasonable will depend on the type of the device. While your goal remains unchanged, the effort that you put into achieving that goal varies with the risk that the device poses.

Achieving the Goal – Planned Maintenance Strategies

Having defined our goal, we now need a plan to achieve it. There are four common strategies for planned maintenance. Most people will operate a system made up of a combination of these:

a) Item-Based

b) Area-Based

c) Device Group Based

d) Opportunistic

Before discussing these points in detail I want to point out a couple of simple things which are worth mentioning: tolerances, and Next PPM Date.

Tolerances

Before discussing strategies in detail it is worth considering tolerances. If a piece of equipment with a annual service interval is serviced on 1/9/2014 at 11:35, then it is next due for maintenance on 1/9/2015 at 11:35. To do it early is possibly wasteful of resources, and to to it late is possibly dangerous. How wasteful or how dangerous is a question of judgement. If you do the maintenance 5 minutes early this is presumably not very wasteful, and if you do it 5 minutes late this is presumably not very dangerous. To do it 364 days early is probably quite wasteful while doing it 364 days late is potentially quite dangerous. For those of you interested in mathematics, this is exactly the kind of thing that fuzzy logic was invented for and there are very interesting ways of modelling terms like quite & fairly.

Your plan should define what is acceptable, both in terms of doing maintenance early and doing it late. This likely to vary with the type of device and its usage. Late & early may well mean different things for a defibrillator in ITU or a tympanic thermometer in a ward.

Tolerances are an important consideration. Abandoning an operation half way through because the diathermy machine service is due at 11:35 would probably cause our friend in Clapham to raise an eyebrow.

What does Next PPM Date Actually Mean

If you look at at equipment record and it says that the Next PPM Date is 1/6/2015, what does this actually mean? If, in your entire inventory there are no devices where the Next PPM Date field is before today, does that mean you are 100% compliant? And while we’re at it, compliant with what?

The equipment Next PPM Date field is, in most cases, a value calculated from the service history for that device. The value the Planned Date of the soonest non-started PPM job. This means that it is the date on which you plan to find and service the device. There is a difference between when you plan to service a device and when it is next due maintenance, as you will see in the next few paragraphs, so the fact that date does not necessarily mean that the device maintenance is up-to-date.

Suppose that you plan to service a device on 1/6/2012. At some point prior to that you search for the device but cannot find it. You may contact the owner of the device and ask them to make it available but there is no guarantee that you will be able to find it. It is very common practice, after some time searching for the device, to abandon the search. Commonly you would notify the owner that you have not been able to find the device and then close the outstanding PPM job with a status of NOT FOUND. This would schedule next year’s job with a planned date of 1/6/2012. This date is when you next plan to service the device. Just because it is in the future does not mean that the device maintenance is up-to-date. In fact, we know in this example that it is at least 12 months overdue.

This is an important distinction. When analysing current compliance the e-Quip KPI’s do not look at the equipment Next PPM Date. Rather, it searches back through the service history to find the last time that the device was serviced. The actual date that the device is next due for maintenance is on this date plus the service interval. Thus, if an item on a 12-monthly service interval was last serviced on 1/6/2010, it is next due maintenance on 1/6/2011. If the maintenance for 2011 & 2012 has been missed then the equipment Next PPM Date will be 1/6/2013, even though maintenance on the item is well overdue.

When we talk about compliance, what do we actually mean? The term, in fact, has two meanings. In e-Quip, especially in the context of the KPI’s, the term current compliance is used to indicate whether the maintenance on a device is up-to-date. In the example in the previous paragraph, the device is clearly not compliant because it has not been serviced since 2011 and it should have been serviced on 1/6/2011. Indeed, it is seriously non-compliant.

The other meaning of compliance identifies how well you have been adhering to your plan. If you planned, for example, to do 500 planned maintenance jobs in December 2012, did you actually manage to do all of them? If not, how long did it take you to actually complete them. You will see in the new few paragraphs that you can be 100% compliant with your plan but this does not mean that 100% of your inventory is necessarily compliant. This would be an indication of what is known as a “rubbish plan”. Your plan is supposed to have been designed to achieve your goal, but there are good plans and bad plans.

Your plan should be able to convince our mate in Clapham that is a reasonable way of achieving your goal.

Item-Based Scheduling

This is the mechanism that you would adopt in an ideal world where you can guarantee that all equipment will be both found and made available. It’s as simple as: when a device is due to be serviced, you service it! Nothing is done early, nothing is done late, everything is done exactly on time.

Clearly this approach is only going to work when you can be 100% certain that you will find the device. If the device is mobile it must be important enough for you to spend a significant time searching for it, so this is more applicable to linear accelators and MRI scanners than tympanic thermometers and syringe drivers.

I want to fly with an airline which service their aircraft this way! Obviously tolerances still need to be taken into account. If I’m flying from London to New York I would rather the engine service was done a few hours early before we take off, rather than half way across the atlantic.

Area-Based Scheduling

An area-based approach is extremely common strategy; quite possibly it is the most common strategy used for the maintenance of medical devices. We identify a particular area and assign a service interval to it. At that interval we visit the area and then find and service all of the devices that we find within that area.

This strategy has some appealing advantages: most notably that many devices will be found and serviced. If the area is relatively small then the search time will be approximately constant (if we assume that a) each device is approximately equidistant from the searcher, and that distance is small and b) the number of devices in each area is broadly similar). Even in areas containing a large number of devices the search time becomes negligible relative to the time spent actually servicing each device.

It has, however, two significant disadvantages. Firstly, because the service interval is related to the area and not to individual devices, there is not necessarily any relationship between the service interval of the devices and that of the area. This means that some items will be found which are not yet due for maintenance, while others will be found whose maintenance is overdue.

The second disadvantage is that the area may contain a wide variety of equipment which has different service intervals. If all of the devices in the area have the same maintenance frequency, then after the first visit the dates that maintenance is due will align with the date that the area is visited (assuming that devices never move). But if 50% of the devices have a service interval of 12 months, 25% are serviced every 6 months and the remaining 25% serviced every 3 months, then only the first set of equipment will be efficiently maintained. The remaining 50% will be sometimes serviced early, sometimes late, but only infrequently on-time.

When we consider mobile devices it becomes possible for a device to greatly exceed its service interval. Indeed, as a device moves around the hospital it may never actually be serviced, unless by coincidence it finds itself in an area precisely when that area is due for maintenance. Here we have a situation where you may be achieving 100% compliance with your plan and yet still have equipment in use which has not been correctly maintained.

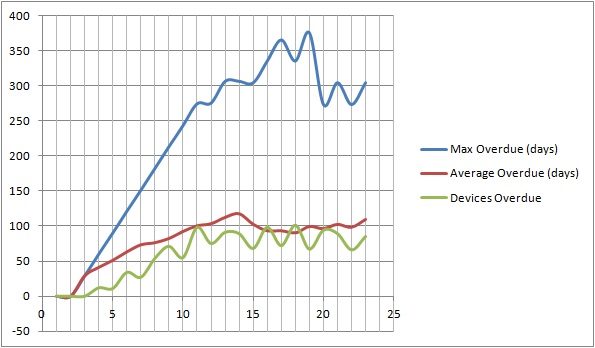

The chart below shows the results of a PPM simulation program that I wrote. This assumes an inventory of 12,000 assets dispersed equally (initially) around a hospital of 12 locations. Each location is serviced on a 12-monthly basis, and at the start of the simulation the maintenance on all items was fully up-to-date (i.e. assets in Location 1 were all due on 1/1/2000, those in Location 2 were due on 1/2/2000, etc). If no devices ever move this schedule is perfect. However, the simulation assumes that 0.5% per month(i.e. half of 1%) of the devices move each month. Each device is equally likely to move and the move is to a random location. Each service visit is 100% successful, i.e. every asset in the location is found and serviced.

The number of devices which are late for maintenance rapidly rises and then starts to oscillate between 75 & 100, so things get bad quickly, and then things stabilise with 75-100 devices overdue maintenance at any one time.

Of the devices overdue maintenance, the average degree of lateness climbs rapidly and then oscillates at around 100 days, or just over 3 months late.

The maximum amount that any one device is overdue climbs steeply to a value of about 275 and then oscillates between 275 & 350 days. This is quite an alarming result. Theoretically you are 100% compliant with your plan, but after 10 months of running the plan you can pretty much guarantee that you will have 1 or more devices which are almost 1 year overdue for maintenance.

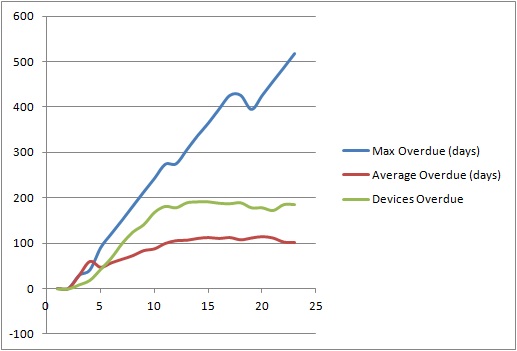

The chart below shows the results of the simulation when the number of devices which move is changed to 1% per month.

Device Group Scheduling

This is perhaps the next most common approach after area-based scheduling. With this approach, devices are grouped by some common attribute (such as model, or contract) and a service interval is assigned to that group. At that frequency you then generate a list of the equipment in that group and then attempt to find and service each of them. Some examples are shown below:

Device-specific maintenance plans can have the advantage that each device is serviced only when it is due. If you achieved 100% compliance with a plan of this type then you can be certain that every device has been correctly maintained. However, achieving this compliance becomes significantly harder. Search times are no longer constant and will not necessarily be small relative to the time spent actually carrying out the maintenance. Each device is no longer equidistant from the searcher and the distances between the searcher and the devices can become large. With this type of plan the probability of achieving 100% compliance decreases as the average device search time increases.

When implementing device-specific plans you must be careful that the way in which you group the devices does not introduce similar problems to those found with area-based maintenance. While the grouping is based on model or category this is unlikely, but if the grouping is, for example, “service all equipment on the ARJO maintenance contract every August”, then if the devices affected are of widely different types with different service intervals, this would perhaps not be appropriate.

It is precisely because of these advantages and limitations that many medical device managers implement a hybrid plan which combines both of these strategies. i.e. some devices will be maintained using area-based schedules while others are maintained with device-specific schedules. By far the most common types of device-specific schedules are model-based and contract-based. Normally, contract-based PPM schedules apply only to devices which are maintained by 3rd-party companies, but it is relatively common to see SLA-based scheduling, where a Service Level Agreement is broadly equivalent to an internal contract.

Believe it or not, this is how lots of hospitals used to do planned maintenance. You have a hospital full of equipment and when something breaks the user brings it to you. You fix it, and while you have it in your possession you do its PPM. Very commonly you would stick a label on the device saying something like “Next Maintenance Due on 25/9/2015”. If you were really lucky, sometimes users would read the label and bring equipment to you when it was due to be serviced.

As strategies go this doesn’t have a lot going for it, but many people incorporate this approach into their plan. The reason is clear – “no plan survives first contact with the enemy”. You might plan to service a device on a particular date, but while you actually have it in your hands when you’re repairing it, are you sure that you will be able to find it on its planned maintenance date?

Using this strategy as a backstop to catch some of the things which don’t get caught by the others is a good idea. Relying on this strategy solely is a very bad idea. I think I would pass up the chance of a flight with an airline which only did this!

Evidence

Recall that part c) of our goal was to keep sufficiently detailed records that you will be able to convince the man on the Clapham omnibus that you have taken reasonable steps to ensure that your devices have been maintained responsibly. This means that you must be able to provide evidence of what you have done. Simply recording what you have done is not likely to be sufficient; it is equally important to record what you haven’t done, including a) why you didn’t do it, and b) what subsequent steps you took.

This true whether you use area-based or device-specific scheduling. If you visited ITU in February and serviced 500 devices, then recording that fact is only one part of the evidence that you need to record. You should also keep a record of the devices which you expected to find in ITU in February. If some of those could not be found then you should record that fact, for each device. If there were some devices which were found but could not be serviced because they were in use, then that fact should also be recorded, again for each device.

If you fail to service a device for any reason, what should you do? A common procedure is to inform the equipment users of this to give them a chance to either find the equipment or to make it available. A very common dialogue between a device manager and a device owner is:

a) “We will be visiting your area for the purposes of planned maintenance on (some date). Please make the following devices available: …”

b) “We recently visited your area for the purposes of planned maintenance. The following devices were either not found or were not made available:… We will return in (some time) to service these devices. Please make them available”

c) “We recently visited your area for the purposes of planned maintenance and despite reminders the following devices have still not been made available to us:… We will now …”

Of course, what follows the “We will now …” cliff-hanger is entirely hospital- and device-specific. Whether it is “… now close the hospital” or “… now our entire team will commit ritual suicide” or “… will come back next year. If you do find the device please don’t use it and contact us so that we can carry out the maintenance”. I will leave it to you decide which the chap from Clapham would find most reasonable. The most important thing is that:

a) You have a policy

b) You have records to demonstrate that you complied with that policy

Different Forms of Evidence

How should this evidence be recorded? e-Quip offers 2 choices:

a) Manually annotate equipment records with this information

Equipment Record Annotation

The 1st option is effectively equivalent to having a paper equipment file and writing notes on that file to record this kind of information in a textual way. The advantage of this is its qualitative nature: because it is textual it allows long narrative descriptions which describe a sequence of events. This is also its principal disadvantage. Because of its qualitative nature it is subject to errors and cannot easily be searched. That said, it is still evidence and it does have its place in your overall record-keeping strategy.

We do attempt to allow some quantification by providing 2 fields on the equipment record which can be manually updated: Last PPM Date & Next PPM Date. Normally these dates displayed in these fields are calculated from the service history, but they can be manually entered. These fields at least impose a certain level of validation on the data that is entered, over and above simply typing dates into notes fields.

This approach is most suitable (in my opinion) when maintenance is carried out on a large number of devices by an external contractor. Suppose that as part of your inventory you have 2,000 suction controllers and O2 flow-meters. You may have a maintenance contract with a 3rd-party supplier to visit annually to service these 2,000 devices. The contractor’s staff may be on-site for a month or more, moving from ward-to-ward servicing each suction controller and O2 flow-meter that they find. On completion they may leave you a paper record identifying (by serial number) all of the devices which they found, where they found them, and the date on which each device was serviced. If the contractor has an up-to-date equipment schedule for the contract then they may leave you also with a list of the devices that they did not find, but this is probably quite rare.

To record this using the service history would be quite time-consuming. You would need to create completed PPM job for each device that was found and enter in it the date that the particular item was serviced. You would also need to create a similar job for each device that was not found, this time using a job status (such as NOT FOUND) to indicate that the job item was not serviced. In order to provide the evidence that each job was actually completed you could scan the service report left with you by the supplier and attach it to every job.

(This point is laboured for the sake of example. As you would expect for such a common task, e-Quip provides a number of tools & utilities that simplify this process)

There is some validity in the following argument: “If I update the equipment record for each suction controller & O2 flow-meter with the date that it was last serviced (in the Last PPM Date field), then add 12 months to that and record that date in the Next PPM Date field, and also attach a scanned copy of the service report to the contract, then I have evidence that these devices have been maintained and I also have searchable maintenance dates on the equipment record that I can use for reporting purposes. This has saved me the trouble of creating 2,000 jobs”.

The statement is true to a certain extent. However, leaving aside the problem that data errors are likely to be introduced with all this manual date manipulation, it becomes much harder to query historical data. If a device is serviced on 1/1/2005 then with this approach, its Next PPM Date would be 1/1/2006. This date will never change until it is next serviced. The only way to find equipment which has missed its maintenance is to subtract the Last PPM date from the current date and report items where this value is more than 12 months. Finding what has been done is relatively simple, but finding out what has not been done is difficult. In many situations an auditor may well be more interested in what you have not done rather than what you actually did.

A further problem is that this approach only records information for 1 year. When you enter “1/1/2005” in the Last PPM Date field, you are erasing the value that was there previously. The only way that you can now find any evidence for previous maintenance events is by searching through paper (or scanned) documents.

Thus, you have evidence, but it will be extremely difficult to search for anything other than the most recent maintenance for a device. You could counter-argue that you would only need this evidence in the case of judicial proceedings which are only likely to arise after a serious incident. In this event, which should be relatively rare, you would be prepared to take the time to search through your scanned service reports. I would counter-counter this argument by saying that if your data is easily searchable then you are more likely to identify that the device has not been serviced and thus take steps to prevent the incident occurring in the first place.

Either way, as long as the limitations of this approach are taken into consideration, you may find that this is an appropriate method to adopt to manage the planned maintenance of at least a portion of your inventory.

Deriving Evidence from the Service History

For the majority of your inventory I would recommend that the equipment service history should lie at the heart of your plan.

Looking Backwards

Let’s start by making an assumption that you always create a job to record any significant maintenance occurrence for a device. If the device is faulty then you create a repair job and if it is due planned maintenance then you create a PPM job. Using this information e-Quip can calculate both the last repair date and last PPM date for any device; it is simply the date of the most recent corresponding job. In this way, the Last Repair Date and Last PPM Date fields on the equipment screen become irrelevant; they simply show the results of calculations based on the service history.

This clearly takes care of the evidential aspects of your plan, but how does it help with the planning aspect. i.e. what about the Next PPM Date?

Well, you could take an extremely simplistic view and simply assume that all devices are serviced annually, so the next PPM date is simply the Last PPM Date + 12 months. In this case, to find all the devices which need to be serviced in January 2014 you simply search for assets whose last PPM date is on or before 1/1/2013. This looks like a very ugly approach and is making the rather sweeping assumption that all devices share the same service interval. This is clearly not a solution that we would recommend.

Taking a slightly less simplistic view, while it may not be true in 100% of situations the discriminating factor for device service intervals is most commonly the model. Most Peugeot 608 2.0 diesel automatics in the UK have a service interval of 20,000 miles. It may be the case that in some uncommon situations (such as when used for motor sports or for extremely high or low annual mileage) this might not be the case, but most commonly the service interval is 20,000 miles. If you are not concerned with the rare exceptions then there is an e-Quip feature which allows the historic service history update your equipment next PPM date. It is possible to associate a default service interval (in months) to any model. If you do this, then, in the absence of any other scheduling technique, whenever a PPM job is completed, e-Quip will add the default service interval from the model to the completion date of the job, and will write the result to the equipment Next PPM Date field. This is still a very simplistic approach, but it combines the evidence inherent in your service history with the ability to plan your work.

(Incidentally, if you are considering of using the Peugeot 608 2.0 diesel automatic for motor sport I would urge you to think again, and would hope that you know more about medical devices than you do about cars)

Looking Forwards

All of the PPM strategies which consider only the historical part of the service history are relatively simplistic. In order to adopt more advanced approaches you need to accept the concept that the service history can not just contain a list of jobs which have been done, it can (and should) also contain jobs which are planned for the future. This is a big step for users who are new to the way in which e-Quip schedules planned maintenance jobs. In e-Quip history extends in both directions: past and future. That part of the service history which lies in the past forms the body of your evidence of what you did (and didn’t) do. The part of your service history which lies in the future is your plan. Consider the job Planned Date field; any job for which this date is in the past indicates work that you should have done, any job for which this lies in the future is work which you plan to do.

Recording what you did or didn’t do is simply a case of changing the job status, while recording when you did (or didn’t do) it is simply a case of entering a date. I often use the analogy of an appointment card for a dentist to illustrate the concept. This card holds the date of every one of your past visits to the dentist (i.e. your service history) but is also shows the date of your next visit. The analogy with dentists is actually quite useful and extends even to quite complex scenarios.

The crucial point is that if your service history extends into the future, then it is possible derive from it the planned date of the next scheduled maintenance job for a device. i.e. the service history can be used to calculate both the last and next PPM dates. The big advantages of this approach is that:

a) You have evidence of what you have done

b) You can see what you plan to do in the future

c) It becomes trivial to record what you didn’t do

e-Quip has been designed primarily to rely on the service history for both evidence and planning. Indeed, whenever a scheduled PPM job is completed then e-Quip can automatically create the next scheduled job. Here, the analogy with the dentist still holds. As you leave the dentist the receptionist makes your next appointment. Similarly, the act of completing a PPM job automatically creates the next. Importantly, the same is true for PPM’s that you don’t do. If you cannot find a device and so close the job with a status of NOT FOUND or NOT MADE AVAILABLE, e-quip will again automatically create the next scheduled PPM job for the device.

Summary

I have covered a great deal in this article, probably more than is readable in a browser. To summarise:

1. Have a goal

2. Design a plan to implement that goal

3. Implement the plan using a combination of:

a. Item-Based Scheduling

b. Area-Based Scheduling

c. Device-Specific Scheduling

d. Opportunistic Scheduling

Make sure that you collect evidence that supports your endeavours to try to implement the plan. The best way to do this is to use the device service history. The portion of the service history which is in the past represents your evidence of what you have (and haven’t) done. The portion which is in the future represents your plan.

e-Quip works best if the basis of your planned maintenance regime is embedded in your service history.